Jacques Franck is a specialist in Leonardo da Vinci who has trained both as an art historian and as a classical painter. A consulting expert to the Louvre, the Armand Hammer Centre for Da Vinci Studies at UCLA, and other institutions, he has spent almost fifty years immersed in the Italian master’s body of work. Franck has made “critical copies” in order to better understand DaVinci’s techniques, which have been shown at the Uffizi, and has dedicated his life to raising awareness about the dangers of restoration based on insufficient knowledge. He spoke to Mia on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the death of DaVinci and his major retrospective exhibition at the Louvre bringing together almost 120 works from the most prestigious European and American institutions.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

So, you have been working all your life attached to DaVinci. We are lucky to be doing this interview in Paris. As I understand, as we look at the paintings in the collections at the Louvre and the paintings that DaVinci brought to France, it's like a love story, the Mona Lisa which he keeps close to him. As I understand, speaking to you, your relationship with him is also like a love story.

JACQUES FRANCK

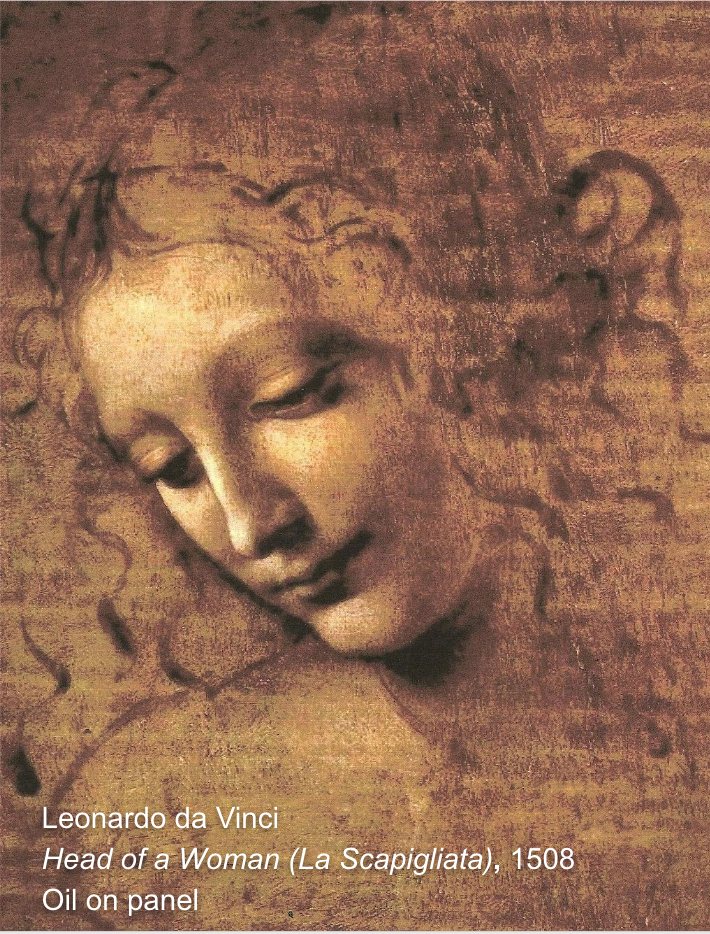

Yes, well, more or less so but I was a little child actually when I first saw Leonardo's work. That work was the Mona Lisa, on a photograph, that was shown in a book. Well, that's many years ago. I must have been seven or eight years of age. It struck me immediately as if I had already seen that picture, and it seemed to me absolute perfection. It struck me mostly because of the wonderful sfumato of the flesh and the presence of the figure, of the sitter, as if she was there. Then I considered immediately, not having much culture about Renaissance painting at that age, that Leonardo was probably the most important artist in Western art.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

What for you made him the definitive artist of the Renaissance and Western art?

FRANCK

The sense of perfection in every sense. First of all, spiritual perfection, the expression in the portraits. The sort of deep understanding of the human soul. Also, when representing sacred subjects, representing the divine as though he had been able to see it. Just in front of God himself in a way. Because the expression in Saint Anne's face is so Christ-like and the expression of divine love over humanity. And this is very seldom represented in art. So this extraordinary way of representing this supreme feeling and also the perfection in the shaping, and the composition and everything was perfect with him.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes. Perfect and yet human. He gives a deeper humanity.

FRANCK

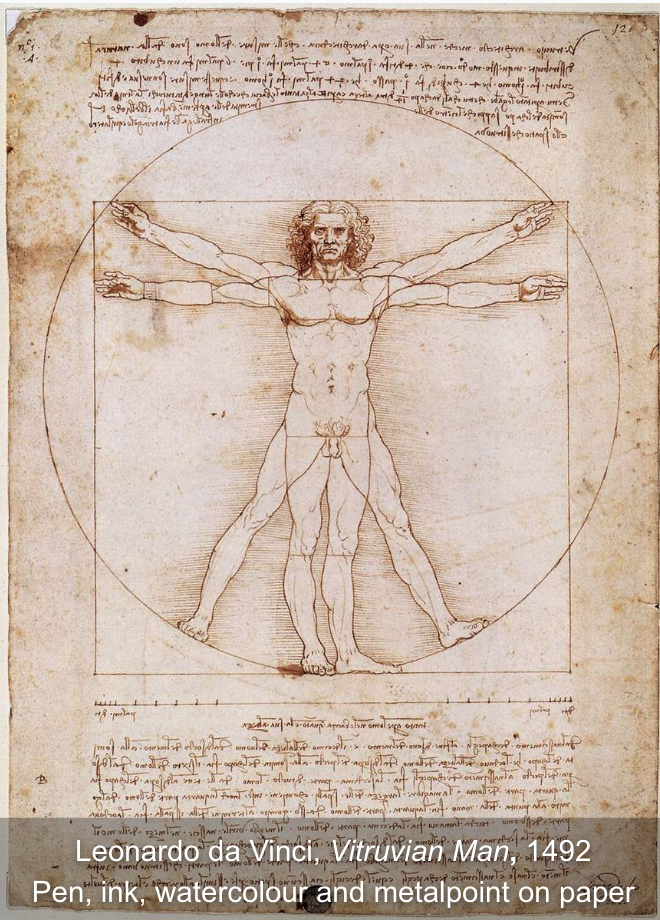

Yes, human. Yes, well, he has both. He'd been painting all his life, and he was a researcher in his soul mostly. Painting was a means to question the universe. In order to make his art as perfect as possible, he would know everything that he could put into his paintings. So everything on perspective, everything on optics and mathematics, everything on the ingredients that have to go into the making. Everything about geology, because it has to be represented in a very accurate way in landscape painting and so and so forth. I don't think that Leonardo had difficulty in imposing himself as an artist because he was so, I should say divinely, gifted, that it struck everyone that he was a genius at once. And that occurred in Verrocchio's studio when he entered the workshop at the age of let's say 13 or so. He'd been already creating and painting and modeling because he was a sculptor also. He impressed his master Verrocchio. And, of course, he needed to have further academic training to learn all sorts of essential topics that were needed for proper instruction of a good painter. All this was rather easy, I should say. At the age of 30, he was a famous artist.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

And in Verrocchio's studio. Now he stayed there quite a while, too?

FRANCK

Yes, quite a while. He stayed there for at least 10 years.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

He also was picking up, I understand–and I don't know if that was unique for other ateliers at the time–but a lot of engineering knowledge.

FRANCK

Yes, in addition, because he was very much interested in these matters because the Duomo, Brunelleschi's in Florence was still on its way to be built up, it wasn't entirely finished when Leonardo was young, let's say by 1470. So he could see all the workmen and architects and all these people cropping around in a building and Verrocchio was invested, too. He had commissions because these botteghe had different possibilities. There would be architects, there would be sculptors, painters. They had all sorts of crafts. So Leonardo could pick up a lot of knowledge, information, and training during these years in Verrocchio's workshop. When I got into the Beaux-Arts school in Boulogne-sur-Mer, I was taught architecture, I was taught sculpture, and art history at the age of 13. Further on, I wanted to know everything about poetry, literature, acting.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, you were London . . .

FRANCK

Yes, on the stage in England. And all these things because every discipline is helpful to the other one. I could never have had the patience I had to recreate the Saint Anne, although I had already guessed, rediscovered the technique. It's not the technique enough, it's a piece of art, so you've got to be as high in the artistic level as possible. At that time, I was making this, I was also writing poetry, and I was very much inspired by French symbolism. Someone like Mallarmé, who was a great, great poet, had a way of writing his poetry, quite extraordinary. He would create his poetry very much using words and not paint. Like Leonardo did, which means very chiseled. The thinking of which word will go with another word in order to create both sense and harmony was extraordinary. And if I hadn't been focusing so much on Mallarmé's way of writing poetry, I don't think I would have had the patience to spend three thousand hours on this copy. Because his famous poem Hérodiade, he spent 40 years writing it. When Paul Valéry, who knew Mallarmé well, although he was younger, said when he first saw Hérodiade, he said, "I was so shocked, so impressed by the perfection of this poetry because it was so perfect that the images in that poetry were absolutely clear, would be striking you, get into your memory and then, once you'd read that poetry you could remember it without making an effort because it was so perfect it's something you couldn't forget. Of course, I was a painter having my own style.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes.

FRANCK

When I started copying Leonardo, it was an exercise to learn. It's like a man who would try to climb up the Alps or the Everest mount you see, because Leonardo is so mad. But I knew that that way I would learn something important because he was such a high level master. But then I tried to learn out by myself. I was taught by Demizel, who's the man who painted this landscape of post-impressionist of high level, trained in the late 19th century. But I had to go all through the process of, first of all, working, trying to understand what art is about, trying to create, make oneself a technique and also know, finally, what is the right level. Art should have... Rigorousness in art is based on something that has been sort of schemed I should say by Paul Valéry. He says, "La seule réelle dans l'art, c'est l'art". The only thing that is real in art is art itself. So the logic in art is art. So one has to understand what art is.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Inside out learning, yes.

FRANCK

Yes. Well, in itself,and it's a level. I mean it's something like Holy Grace. You've got to come across it, and then you see what it means. And it can only come like a revelation, it only comes like something that is what it is. And you know what it is not. You can't go and penetrate such high intellectual spheres unless you are a man of good. Do you understand what I mean?

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes.

FRANCK

To have some ideal of perfection, beauty, and humanity inside yourself. Well, I have always considered Leonardo as the perfect artist, and more or less like a father. The real master is a kind of a father figure. So, to help me understand better, improve myself, know more, make the proper efforts and listen to someone who is so knowledgeable that in listening to what he says you will make real progress. I was listening to Maria Callas some time ago, because when she came to Paris in 1968 she was in the Opéra Paris, and she was in a concert. She could sing well still. So I looked at her and Callas had been training very much, if you know about her biography, she started as a little child and she was so keen on opera music that when she was going to bed at the age of eight, nine or so, she would take a small lamp under the sheets in her bed, because her mother wanted her to sleep. She would follow old musical parts of the romantic 19th century period just to get information and be very knowleged about these old parts that no one would ever sing again in the 20th century, because she rediscovered Bellini and all these parts, you see. Music was in her psychology. In Leonardo, art was in his psychology, as an expression of the mystery of life in him. The same in Callas. I'm always observing artists performing because it's very interesting to observe. She was living in another dimension. As if she were connected to an invisible source, and that invisible source suddenly gave her genius. On top of all she'd been learning technically, so she had the art, the architectural setting of the technique. So she couldn't fail, because of course what she was singing was very difficult, but also, suddenly, life came into it. And this is what makes the difference between artists and those who are not artists. If you really wish to be at the highest level, you've got to consider that perfection is just a base. And in these times we really had that sense, you see, today it's more or less, "perfection is something that stops me from being myself". If you think that way, you'll never reach what you are aiming at. You must renounce to something that is in you, to let out the best. It's logical and mathematical. If you want to have really the top inspiration, you've got to focus your mind on the highest value in aesthetics. Art is art, and that's all. To me, art is the expression of beauty, and beauty is something like the sun, shall we say. An absolute.

This interview was conducted by Mia Funk with the participation of collaborating universities and students. Associate Interviews Producer on this podcast was Ally Chou. Digital Media Coordinator is Yu Young Lee. “Winter Time” was composed by Nikolas Anadolis and performed by the Athenian Trio.

This is an excerpt of a 15,000 word interview which will be published and podcasted across a network of participating university journals and national arts/literary magazines.

Mia Funk is an artist, interviewer and founder of The Creative Process.