How can the arts inspire us to lead lives of greater meaning and connection? What kind of world are we leaving for future generations?

Julian Lennon is a Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter, photographer, documentary filmmaker, and NYTimes bestselling author of children's books. Executive Producer of Common Ground and its predecessor Kiss the Ground, which reached over 1 billion people and inspired the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to put $20 billion toward soil health. The natural world and indigenous people are also the focus of Julian’s other documentaries Whaledreamers, and Women of the White Buffalo. In 2007, Julian founded the global environmental and humanitarian organization The White Feather Foundation, whose key initiatives are education, health, conservation, and the protection of indigenous culture, causes he also advances through his photography, exhibited across the US and Europe. His latest album Jude spans a body of work created over the last 30 years. Julian was named a Peace Laureate by UNESCO in 2020.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

Congratulations on the documentary Common Ground of which you are an executive producer. I just saw it and it's an amazingly personal and informative film/series/movement now and with so many people involved being a voice for nature and speaking up for soil that sustains life on Earth. It blows my mind when I think about it, it's kind of magic that one teaspoon of fertile soil contains more living organisms than there are people on the planet! Tell us a little bit about the genesis and mission of the film Common Ground and how you were drawn to the story.

JULIAN LENNON

I thought, wow, how are they going to bring this across in a way that isn't shoving things down people's throats? It's presenting information in a way that is creative, but also in a way that drives your curiosity into understanding, number one, why are we in the position that we're in? And number two, how can we fix this? What can we do to change all of this?

And so, I initially got involved as an executive producer on Kiss the Ground, and I was blown away by how that film came out at the end. How well rounded it was, the flow of the film, the storytelling, and really feeding me information that I didn't even know previously. And so, and also watching that become a platform around the world was jaw-dropping. I mean, the fact that the belief and the understanding and the wisdom that came out of that project has touched so many hearts, minds, and souls around the world, that people are really single-handedly almost making change for the better around the world.

Now, when Common Ground was presented, I did love that concept because Kiss the Ground had been very much a broad approach and about America, for the majority, really, and Common Ground was a much more...I mean, we're still dealing with the same subject matter obviously, but I think it felt great to come from a more personal aspect.

With this film in particular tugging at people's hearts, regarding family. I mean, really trying to get the point across that this really affects all of us in every way, shape, or form, and that, you know, if we don't do anything...It seems to me that since the beginning of time almost, at least in the corporate world, there's always been walls put up for anything that's organic, positive, natural, and the list goes on. And I think that filters down in many fields. And so be part of something, a positive movement that continues to do such great work, I just keep my fingers crossed. And obviously, my job here as well is to support in any way, shape I can.

And of course, I believe in everything that's being told. It is the truth. These are the facts of our lives at the moment. And, if we don't look after Mother Earth, Gaia, she can't look after us. It's a shared experience. It's a balance between things, everything in life. You know, we need each other.

Everything affects everything else. So it's key that we all take part in trying to make this place a better world for everybody. And, you know, when you see the logic behind the fact that it is possible to feed the world. It really is. And it's possible to make so many positive changes. You know, I've always been an advocate for, of course, trying to protect indigenous peoples around the world because although their logic may seem simple, it works. It's real. It's respect, not only for one another, it's respect for the Earth that we live on and that can be the only way forward that this is all going to work out. I get frustrated at the fact that I don't see why so many people just don't understand this. It's key.

Gabe brown · Jason momoa · donald glover · Rosario dawson · Rebecca & Josh Tickell

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

Of course, you've been a filmmaker for a number of years, focusing on indigenous stories and environmental issues. I think that's what those films, and what Common Ground puts across so well is we see the health benefits, the difference between healthy soil from regenerative farming and dead soil from industrial farming. There's a spiritual sense in this, too. And we just have to relearn what we've forgotten or been brainwashed by the agrochemical lobby to forget. We have to stop killing the soil that feeds us. There are many positive statistics in the film but one that stayed with me was that if the whole planet adopted regenerative agriculture, we could sequester all the carbon that we're currently emitting.

JULIAN LENNON

We're polluting the seas and the waters. We're polluting the soil. We're polluting every aspect of our lives. So there's no getting away from it. That's absolutely sure. And yes, there is absolutely a way forward to make change. And yes, it is a question of relearning so much, without question. I mean, part of the reason that not only did I start the White Feather Foundation with indigenous tribes in mind back then. And then, one of the key ways forward for me was education, of course. I think that's been part of our problem worldwide. People just haven't known how serious or taken it seriously enough before. And there's so much propaganda that's misinformation that's pushed out into the world. You see in the film as well how the truth gets pushed away and shoved aside by money and greed and corporations. And that's a really difficult one to get over, but, you know, writing the children's books was a way to get in the same theme. Again, not shoving it down their throats, but presenting the situation as is and getting children to say...Reading and asking and reminding their parents, and relearning as well. Why is there plastic in the water? Why don't they have any water over there? Why, do you know, why? And there are answers for all of this, and the parents need to pick up on that too.

But this should be made, you know, these two films and many more should be mandatory. I mean, you want to talk about Clockwork Orange...I don't mean pinning their eyes back, you know, forcing them to watch the film, but certainly, this really should become part of the curriculum in many ways.

I hate to use the word logic all the time, but if you're not ignorant and you have an understanding about the world around you, then you know how you can help it. You can know how to make changes and how to move forward. And this is exactly what these films do.

So, may that Josh and Rebecca and everybody who supports them continue moving forward and making more films because until things change, which they are changing, thankfully. I think it's a real credit to Josh and Rebecca, how many lives they've changed and how many eyes and ears they've opened through the course of their filmmaking.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

Speaking about your environmentalism and your children's books, which have been all about the Earth - Touch the Earth, Heal the Earth, Love the Earth, which could be seen as like an entryway into the adult audience for Common Ground and your other films. You point to something being wrong with our global Capitalist system. And you've spent so much time in your documentary work and your photography, visiting Indigenous peoples. You know, colonialization just didn't take over the lands, but language was lost. And with that Indigenous intergenerational knowledge. I know that you made the film Women of the White Buffalo, which is about the Lakota people. And I always remember something Tiokasin Ghosthorse said. It's quite powerful. When you think about the Lakota language being a language of verbs and not nouns and ownership. "Dogma and domination have no relationship with the Earth. It's taken us away from the language of the Earth, we have to remember how to speak the language of the Earth."

JULIAN LENNON

This is why protecting the Indigenous around the world has been an important cause for me because of that history, because of their knowledge, and the potential of losing it forever. I know that around the world that there are groups that are striving and doing the best that they can to maintain and hold onto those languages, doing as much research and capturing as much of that knowledge as possible. You know, fortunately, there are some incredible, dare I say, youngsters these days who are learning, who have such respect for their elders and their history and their past. They are learning the language and holding onto it as best as they can. As I said, I think the fact that it's all being recorded now and put down, and hopefully nothing further bad happens. I think it's key because we've learned so much from the Indigenous. You know, we're part of that history. It's just we've lost our way. They still know where they're going. It's just the rest of us that have been misguided, I would say, in the bigger scheme of things. The other thing was we, you know, for many, I mean we didn't know any better. That's no excuse, but, you know, we all rode on that bandwagon too of enjoying life to the extremes before we knew, really what that meant, how that abused not only people but the Earth. And the situation that we live in, as you see in the film also, I think we're only just seeing the tip of the surface really about the quantity of illness that is coming from the past 50 years of the way things have been done. I mean, the general public didn't know about so, so many of the bad things that were happening. The poisoning, the chemicals in our food, in all of our products, whether it's from, deodorants to hairsprays to makeup. It's really only in the past few years that there's been a decent should I say shift in that world and that finally some companies are taking responsibility for their actions and their positions, and they're trying to change things too. So little by little, little by little, but, but it's working.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

Your environmentalism, of course, goes way back. We hear in your songs like “Saltwater”. Tell me a little bit about founding the White Feather Foundation. I believe its name has a deeply personal significant meaning.

JULIAN LENNON

The song "Saltwater" was number one in Australia and top 10 around most of the world, except for America, where the label I was working with did diddly squat, so nobody really heard it there, but I was number 1 in Australia. We're touring in Australia and in Adelaide, I was called down by the hotel management saying we have an indigenous tribe down here with a couple of international camera crews with a bunch of people. I don't know, 30 people maybe, and they want to talk to you. And I'm going, what about? Because, you know, I was just on the road, and I thought that perhaps, as people do on the road, they play gags on each other, you know. It's a common thing on the road. So I thought it was a joke that there was a group of Aboriginals downstairs.

Anyway, the management calls up, I go down, and lo and behold, there's a semicircle group of Indigenous peoples called the Mirning people. And it was on a small step-up platform, and I walked towards them and the elder, Iris, who's a female, walked up to me with a male swan's white feather, which is about yay big. And I'm thinking, What is this? What's going on? And she says to me, "Can you help us? You have a voice." And what hit me was that many, many, many years ago, Dad had said to me when we were together, that if something were to happen to him, that the way he would let me know that either he was going to be alright, or that we were all going to be alright, would be in the form of a white feather. So when, you know, I'm given this white feather by one of the oldest peoples on the planet, to me that was undeniable. Goosebumps. I just thought, if that's not a sign, I don't know what is, you know? If that's really not a sign. I don't know what it is. So I just said, "Okay, I'll do what I can for the children."

And so I spent on and off, 5, 10 years making a documentary called Whaledreamers about not only the Mirning tribe, but it tied into another film project that the director and I were working on called The Gathering, which is where we brought together 80 elders from around the world, from all the indigenous, as many as we could get in from around the world to meet together around a fireplace and to, you know, talk about their woes and the problems that they have had, and they were all the same. They were all the same. Used and abused, murdered, you know, thrown off their land. The list goes on. And so, it was difficult making the documentary because it was the birth of the Internet. And so the part of the team, the editor was in Byron Bay in Australia, and I was here in Europe. So editing took forever. Anyway, once the film was finished, we were lucky to get a small screening in Cannes, but we won about, not that this is important, but we won about eight independent film awards. And I just thought, Okay, well, you know, if the film makes some money, I really want the money to go back to the Indigenous tribes.

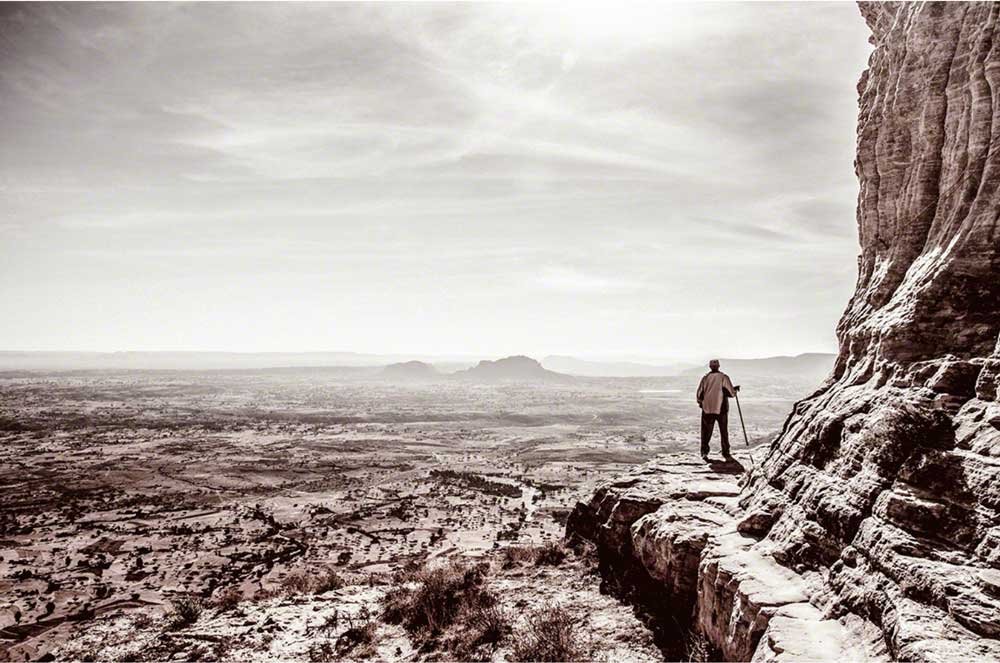

And one thing led to another and I started getting emails saying can you help us with this project? And can you help us with this project? And then I thought, well, maybe I'm in a position where I can continue this. Maybe I can do some further work and good. And so I just thought about the things that were most important to me, looking after indigenous people, cultures, and their land was really important. Clean water, absolutely essential. Obviously, health and education was a massive one. All of that, a lot of that came out of the travels between South America with the Kogi, going to Ethiopia, and the different processes - actually with an organization called Charity Water with Scott Harrison who took me out there to see the wells. The before, during, and after the water wells had been brought to life. And in Kenya, going to schools and health clinics, and being there with the kids. And it was the UN Millennium Villages Project that we were tied in with. That's where it all came from. What touched me the most were those particular subjects. And so, we're, we're a small foundation, and I don't want to be a big foundation. We tend to capture the people and the causes that fall through the cracks, you know. It's all the little projects that nobody seems to get around to, and we live on donations from the public. I mean, that's predominantly how we survive, and how we help people around the world. I mean, all over the world. So it's been a blessing in disguise being able to be fortunate enough to help people out around the world and work on the White Feather Foundation and be part of projects like this, too. So it's a meaningful life.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

I've been enjoying also your recent album Jude, and your music throughout your career. I wonder with all your travels and what we see in your photography, what your future collaborations in music might be?

JULIAN LENNON

I don't honestly know entirely where I'm headed musically. I still have a lot of songs that I haven't finished that are relatively recent and some that go back to 40 years ago, if not more. You know, projects like this last album Jude, partially songs that never had a home, you know, that didn't quite fit on an album or another project. And so, I mean, strangely enough, what I've been doing personally for the end of this year has been going through trying to get all the admin out the way, so to speak. For instance, in the last six months to a year, but intensely so in the last few weeks, I've been archiving over 100,000 photographs of mine so that I can put more collections together, so I know where things are, et cetera, to get on with the creativity of photography next year and hopefully get around to a few more charity trips. Same thing with the music, getting that under wraps on the admin side. I don't want to do work with another label again, I think. I prefer to be in a position, where things organically happen, creatively speaking. So, the idea is to be in a position next year where if I write, record, and produce a song in a few days or a week, that within a week or two or a few weeks, I can press a button and release it out to the world. That's my plan for the future. Probably no albums, probably. EPs and singles, as they come. That's the idea for the future. And to just be as happy and present and as creative as possible next year. And help the projects and people that need help. That's my goal for the future. That's how I am. Because, again, if I'm not in a position of focus and in a position of love, then, you know, I can't help anybody else. So that's my goal is to be fully in that headspace next year.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS · ONE PLANET PODCAST

The film Common Ground begins and ends with a letter for the future, for the children of the next generation. I believe you also may be working on a memoir. So as you reflect on your life and your art, what would you like young people to know, preserve, and remember?

JULIAN LENNON

I think one of the key things that I've certainly earned is that you have to follow your instinct. You have to follow your gut. If it feels bad, walk away from it. You know, I think it's self-preservation. And again, it's the old adage that you can't help, you can't love other people if you don't love yourself. And it's akin to that. For me, it's about love and respect, and respecting differences, too. It's all about the fact that we are all different in every way, shape, or form, but you can still love someone for being different. We don't need to be the same to love each other. And nor do we have to have the same opinions. But certainly, I think it's wise to work together for the common good of not only our Earth but our lives and the lives of all creatures on this fair planet of ours. It's a magical world that we live on. It's unique, again, as far as we know, we're the only ones running around like mad people. And I think we should try and enjoy it as best as we can, and we should try and love as best as we can. And we should try and help each other as best as we can because, in the end, we're all connected in every way, shape, and form. And that is the be-all and end-all of it. We are one. We're all in this together.