What makes great art? Why does some artists’ work continue to speak to us long after they are gone?

“I met Miles backstage at the Hollywood Bowl—the last gig he ever played. Miles asked, “Who’s that white boy?” I introduced him to Bob Thiel Jr., whose father produced Coltrane. When Miles discovered this, he said, “Well, you can hang,” following this friendly gesture with me walking Miles to his car. I did not know he was dying. I kissed him on both cheeks. And 18 days later, he was gone.”

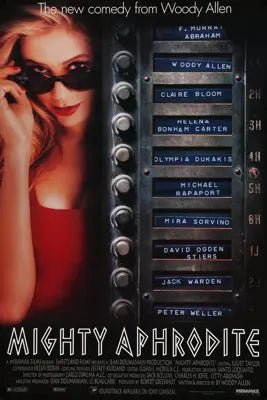

Peter Weller is a renowned theater and Hollywood actor. His performances in films such as RoboCop and Naked Lunch garnered him much critical and commercial success over the years. His television acting and directing credits include Sons of Anarchy, Dexter, and 24. Unbeknownst to most, Weller has spent decades honing his appreciation for the visual and musical arts through his studies of the Renaissance era. Earning a Master's in Roman architecture from Syracuse University before moving on to a PhD in Renaissance Art from UCLA. Dr. Weller has just written a book, Leon Battista Alberti in Exile: Tracing the Path to the First Modern Book on Painting.

Weller has also contributed an essay remembering his friend Miles Davis for Jazz and Literature. The book, co-edited by Mia Funk, features many of her interviews and artworks, as well as poetry, art, and essays by our contributors.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

You've just written a book, Leon Battista Alberti, in Exile: Tracing the Path to the First Modern Book on Painting. What attracted you to Alberti?

PETER WELLER

Leon Battista Alberti is an interesting figure because most people don't know who he is. They think of the Ninja Turtles—Michelangelo, Raffaello, Donatello—all those guys who came out of Florence at one time or another. Subsequently, Florence is sort of the center of operations of the Renaissance, as we call it. Of course, scholars know who he is because he was a polymath; he was a poet, painter, architect, and particularly an architect, writer, and humanist. He wrote this amazing book on painting that everyone has to read. There are two versions of it: one in Latin and one in Italian, which has been translated into English. In front of the second Italian version, there’s a letter thanking several people, including Donatello and Gilberti.

You have to read this; you have to read it. The takeaway from the letter he wrote is that he came to Florence and wrote this amazing book in about nine months to a year. He saw these artists and thought, "Wow, I’m going to write this book," in tripartite Ciceronian Latin, bringing up all of antiquity and addressing lines, points, measures, depth, and color—all these theories—in just a year because he came to Florence and saw these guys. Frankly, when I read this, I find the takes on what Alberti did quite overwhelming. It’s fascinating because it's the first modern book on painting, and it's in three parts. Though I consider myself a mediocre to poor Latinist, I am an obsessive learner. I still feel I don’t know enough.

I read those guys all the time. But Alberti's sources were the Greco-Roman contributions to art and architecture. Come on, this guy didn’t just come to Florence to write this book in nine months. I walk around asking professors, and it’s funny; I ask some well-known people from England all the way to Italy. I say, “Guys, the implication here is that he came to Florence and wrote this book.” I talked to 20 people, and everyone except one—who I'll discuss later—said, "Peter, everybody knows that." I asked, “Well, why isn’t it taught?” It's not taught as it should be; instead, the narrative says he came to Florence and became a smarty pants. Why isn't his history taught? They replied, “Why don’t you teach it?” Five of them said, "You should write it." I asked, “You want me to be the scapegoat for like 40 people coming out of the woodwork?” And by the way, art history competition is truly pretentious.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Yes, I know a little bit about academia through my book projects and podcasts.

WELLER

It’s like what Henry Kissinger said, there's so much competition in academia because there's so little at stake, right?

I have to say I was the Ugly American—I was Mark Twain’s version of it. I was essentially sent to Italy by a friend. I was amazed, confused, and dazed. I would run through Italy, absorbing its food and buildings, and looking at the art but never trying to understand it. There were places I warned people away from; for eight years, I told them, “Don't go to Venice. It's overloaded with tourists.” I was skimming the surface of European culture. Eventually, I was embarrassed into learning the language by a great friend of mine, Philippe Collon, a French Lebanese who said, “Peter, we come to the United States, and we all speak English, but you come to Paris and Rome and we all speak English too.” I thought, “Gosh.” I called Ali and asked, “Look, you speak five languages. What do I do here? I've been going to Italy for eight years now and don’t speak any of it.” She advised me to get someone to come to my house for lessons and to make sure I don’t miss them. You've got to be willing to make a fool out of yourself to learn a language.

Thank God my mother took me to see the Berlin Philharmonic perform Beethoven's Ninth. Thank God she took me to see the flamenco reunion of great performers in the 50s. Thank God she took me to Jazz at the Philharmonic. I didn’t want to go to any of this stuff. Thank God my mother made me play music. She was a cultural addict. My dad gave me the discipline to get up and go. He always said, “You’ve got to go to Italy.” He called it Italy. He said, “You think you’re eating Italian food? You’ve got to go to Italy, sit on the streets of Rome, and have them bring it out to you.”

I did a seminar for the 16th Century Society on Renaissance art to modern film. People went into those churches to see the Sistine Chapel, and that was a movie to them. You have essentially an audience, many of whom are illiterate, who learn through vision. They want to be guided by someone. As Ernst Gombrich said—paraphrasing—“You don’t know what you like.” This whole contemporary art fad, “I know what I like; I don’t like that”—yes, you do. If you don’t know what you like, you might just need someone to take you by the hand to help you understand all the imagery from cave paintings to Piet Mondrian. A banker stood with me in my cigar club saying he didn’t get those big black squares, so I walked him through cubism simply. Thanks to Marianne Calo for explaining the whole Cezanne thing to me.

Cézanne took Impressionism and edged it with black. Usually, there are these greens or fields going up a mountain, and you wonder, “What’s with that?” However, if you look closer, you see that he's edged every single square, rectangle, and triangle in it. The mathematics jump out. I walked him back to that, and then to Piero della Francesca, who was the guy who said nature is all mathematical. If you look a little longer, you’ll see the perfect mathematics in a leaf, in a tree, in an acorn. Everything has perfect mathematics, which is a gift from God.

But later on, you see how the framing of films—particularly by great filmmakers from Italy—has been influenced by art. Scorsese knows how to frame shots because he studies art. Coppola knows how to frame because he looks at art. I once took undergrads through four of The Last Suppers in Florence. There’s a Ghirlandaio, a Del Sarto, a Castagno, and a Taddeo Gaddi, each representing the early stages of the Renaissance. We examined how each framed The Last Supper and the drama set up within it.

What is the color scheme of these Last Suppers? One of my favorites is the Castaño at Santa Apolonia. You should Google “Castaño Last Supper Florence” and look at the explosion of contemporary art in it; it's an incredible framing story.

It’s all movies. I want to share something that feeds me. This is called "Flourish of an Outsider," which I presented at a panel on Venetian Outsiders in Venice for the Renaissance Society of America, which is essentially about the World Renaissance. This is "Flourish of an Outsider: The Brief Brilliance of Antonello da Messina in Venice." Here it is: “as a Johnny-come-lately to Renaissance art, I express gratitude to Vittorio Storaro, Maria Canelli, and the late wonderful Walter Liedtke of the Metropolitan Museum of New York. When I first saw the Ecce Homo, you should Google "Ecce Homo Metropolitan Museum of New York," it struck me. This boxer, a pugilist, represents Jesus with a bad mustache.

Is he handsome? No. Does he look like Robert Redford? No. Does he have blonde hair? No. Does he look like a thug? Yeah. When I first encountered the Ecce Homo at the Met, executed in Venice by Antonello da Messina, the painter instantly became my own private Idaho—a perspective later dismissed by graduate classmates as second-tier, compared to Florence and its Ninja Turtles like Raffaello. My appreciation was akin to heralding Bob Dylan as a real poet in contrast to Cummings, Eliot, or Wallace Stevens in the 1960s.

Thanks to the 21st century, events like Keith Kircherson and Andrew Ibarra at the Met's 2005 poignant exhibit, as well as Mario Luca's brilliant 2000 show in Rome and a plethora of 21st-century scholarship, have revived interest in Antonello. Now, he seems to be everybody’s pet painter of the Renaissance, which I honestly resent a bit. Yet again, Bob Dylan won the 2016 Literature Nobel Prize as a poet, no less.”

The point is that everyone’s perception of an artist does not always reflect the truth. You have to step out of the bubble. My whole thing, thanks to my mother, is jazz. This obsession led me to meet Miles Davis, and during movie interviews, I always turned the conversation back to jazz, discussing Miles, Coltrane, Duke, and others. By the time I met Miles, he knew he had a sycophant walking in, as everyone told him, “This actor guy is constantly talking about you.”

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

I think of you as being a very international maverick. And there's something to your core that’s also very America, coming up in Wisconsin and being at the heart of these very American cities, Los Angeles and New York. You're a strange kind of American. It’s like you’re both an insider and an outsider.

WELLER

My dear friend, Treat Williams, bless his heart, once said to me, “Peter, you know who you really are? You’re a middle-class white boy posing as a black hipster.” I said, “Treat, I think you’ve pinned me.” That’s going to stay with me forever. I am a middle-class white boy posing as a black hipster.

As for what happened next, I met Miles backstage at the Hollywood Bowl—the last gig he ever played. Miles asked, “Who’s that white boy?” I introduced him to Bob Thiel Jr., whose father produced Coltrane. When Miles discovered this, he said, “Well, you can hang,” following this friendly gesture with me walking Miles to his car. I did not know he was dying. I kissed him on both cheeks. And 18 days later, he was gone.

After this, I told my mother what had happened. She said, “You know, if I were God and had to choose someone to say goodbye for all of us, I’d think of a white boy who’s been listening to him since he was 11.”

It resonated within you, evoking happiness and sadness at the same time. I couldn’t believe it. Oh, and Otis has a new album out.

THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Well, that's the outsider thing because you can recognize it because it's something you missed in your own life, but you can recognize it. And I think that's what art does. It speaks across cultures, across time, and, you know, just connects with us before we can even think about it.

WELLER

Art transcends time and culture—the beauty of it. People worry about the world now. I remind them to go live in 1968, a time of preparing to go to the moon while people died for their beliefs. This is a difficult time in a republic that’s supposed to be free, but music was leading the way. Whether it was Miles, Coltrane, Aretha, Leonard Cohen, Dylan, The Stones, The Beatles, or Hendrix, the music was extraordinarily influential and cutting-edge. There was an album—by Zappa, perhaps—coming out every month, and it was all interpretive.

I was just in Japan about nine months ago, exploring the art and dance. We attended a theater performance that required big bucks and advance tickets, and I thought, “My God, the sounds, the drums, the musical instruments, and the absolute harmony amid what seems like chaos to Western ears.” It’s actually harmonious, transcending culture and time. That might be the greatest gift of our transcendence.